Tragic shooting death of a Newfoundland logger in the Scotland Highlands

Reprinted from Downhome Magazine, April 2022

by Lester Green

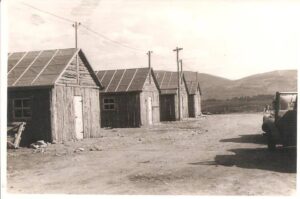

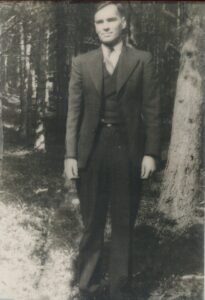

Top Left: Max Hawkins, taken overseas in the Scottish Highlands shortly before his death in 1940. (Courtesy of Tony Hawkins)

A rifle shot that pierced the air in Carrbridge, Scotland, also pierced the heart of loved ones in Glovertown, Newfoundland and Labrador, in the summer of 1940. This is the story of a logger who enlisted with the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit, went to Europe in pursuit of duty and never came home.

On Christmas Day 1909, the lives of Benjamin and Bessie (Penney) Hawkins of Glovertown were forever changed by the birth of fraternal twins: a boy they named Alfred Maxwell (Max), and a girl they called Theresa. Over time the Glovertown couple would add to their family with the arrival of several other children.

Max grew up in a logging town surrounded by loggers. Both his grandfather and father sought a living from the rich forest that lay close to the coastal community. The life of a logger involved long hours of pulling the sandviken bow-shaped bucksaw back and forth across a tree trunk until it crashed to the ground. Then they grabbed the axe and swung it with constant precision, striking the branches and separating it from its trunk. This was repeated from sunrise to sunset, rewarding men with a meagre living.

The Hawkins family. Front (l-r): Edward, Gertie, Margaret. Back (l-r): Theresa, Jessie, Baby Raymond, Max (Courtesy of Tony Hawkins)

When Max was of age, he got a job with the A.N.D. Company, a major employer in the Terra Nova and Gambo region. On November 21, 1939, the Newfoundland Government put out the call for 2,000 lumbermen to serve in Britain to cut pit props. These men would be paid eight shillings a day, with board, lodging, outfits and travel being paid both overseas and return. Logging companies were encouraged to hold meetings to make men aware of this opportunity overseas.

The first contingent boarded the SS Antonia at St. John’s on December 12, and arrived at Liverpool on December 18, 1939, with 300 loggers under the command of Jack Turner. Their goal was to construct campsites for other contingents of loggers that were to follow in January and February of 1940.

Max signed his enlistment papers in January 1940 with the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit (NOFU) and was assigned the number 1840. The men were to harvest logs on the hillsides of the Scottish Highlands for the war effort. This wood was to be used mostly for a product known as pit props but other goods such as lumber and board were produced in sawmills that were quickly assembled around the region. On January 23, he was among the 963 loggers onboard SS Chroby that left St. John’s and sailed for Halifax under the command of Edgar Baird. The ship joined a large convoy of vessels ferrying Canadian troops and supplies overseas. Under the escort of the British navy, they crossed the Atlantic to the Firth of Clyde, Scotland, arriving on the February 8.

The men of the NOFU were to harvest logs on the hillsides of the Scottish Highlands for the war effort. This wood was to be used mostly for pit props. Other goods, such as lumber and board, were produced in sawmills that were quickly assembled around the region. Max was not assigned to cut pit props, however. He was appointed clerk at District B headquarters, Carrbridge Camp, under the command of Superintendent Tom Curran.

Lumberjacks were often given Sundays off, and local newspapers record that on Sunday, July 14, 1940, Max and several other lumberjacks hired a taxi driver to take them on a sightseeing tour that ended in the village of Grantown. The Dundee Courier newspaper records that they travelled to several locations, including Boat of Garten, Nethy Bridge and Grantown.

When they left Grantown to return the camp at 11:00 p.m., it was raining heavily and visibility was poor. The car encountered a person on the road near a bridge that it had crossed. Military regulations required that all headlights on vehicles be darken, which caused the driver to pass a man without seeing him. But the driver abruptly stopped the car when he heard a gunshot. It was only when the driver stepped out that he realized there were to men, both of them sentries. All sentries were instructed to stop everyone, and if the driver failed to stop after being giving three verbal commands, the sentries were to shoot to kill the occupants of the vehicle. It was a time when Scotland was concerned about a German invasion.

One sentry had reportedly shouted three times for Max’s driver to stop before opening fire. The local papers recorded in an interview with the driver, John Ferguson, that there was no red light on the road, which would have been a signal for vehicles to stop. He also claimed that he did not hear anyone shouting verbal commands to stop. It was when the passengers exited the car that they realized Max had been shot. Though attempts were made to save him, they were futile.

The sentry who shot Max was charged with culpable homicide. The case was tried at the High Court of Inverness in September 1940. In court, the driver, Mr. Ferguson, explained that the sentry, Francis Lionel Harrington, got into his car and realized that the shot had struck Max in the back of the head. Harrington then demanded that the driver show him how to start the car, and he immediately drove it to the nearest farm belonging to the Bainoans, where their phone was used to get assistance. But it was too late. Max Hawkins was dead. It was determined in court that even though the sentry may have consumed a few alcoholic drinks that night before he and discharged his weapon, he was only following orders of his commanding officer. These orders stated: “Under present active service conditions, a camp sentry charged with guarding a camp entrance is entitled between dusk and dawn to shoot to kill at any carload of passengers whose driver does not happen to hear three verbal challenges and is proceeding along a public highway in quite unsuspicious circumstances and without any design on the camp.”

Lieutenant-Corporal Albert Pott, commander of the guard unit, claimed that Harrington had carried out his duty. He claimed that if the guards had been issued red lamps to signal cars, the accident would not have happened. All approaching vehicles would have known that it was a road stop, and guards would not have had to rely on verbal commands to stop approaching vehicles. In the end, Francis Lionel Harrington was not found guilty of the charges and was released.

Benjamin, Bessie and their family at home in Glovertown could not even take comfort in the fact that at least the body of their oldest son would be returned from the war. Max was buried in the Scottish Highland at Carrbridge Cemetery, Inverness-shire, Scotland. They would not be able to visit his graveside, but the family did have a memorial stone placed at the United Church Cemetery in Glovertown.

Deadly Miscommunication – PDF – Downhome Article

_______________________________________

Transcribed by Wanda Garrett, January 2026.

These transcriptions may contain human errors. As always, confirm these as you would any other source material