A day on the stagehead in Little Heart’s Ease

Reprinted from Downhome Magazine, May 2023

by Lester Green

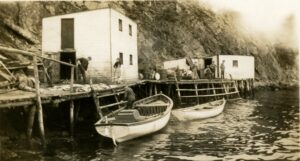

My mind drifted into the past as I looked at this old snap of the stagehead belonging to the Pitcher family, at the now abandoned community of St. Jones Without, Trinity Bay. By the time I travelled by boat to St. Jones Without, my dad’s hometown, the houses, stages, and flakes were vaporized like the morning fog on a warm summer’s day. All that remained was an open field.

The stages reminded me of my childhood days spent on my father’s stagehead at Little Heart’s Ease. We passed many hours catching tomcods and cunners using fish hearts for bait and a bamboo fishing pole. The more adventurous among us would try stabbing flatfish with the prong, often extended by attaching a stick. Sometimes I leaned too far out and fell into the saltwater surrounding the wharf!

A typical summer’s day would start with the early morning fog retreating from the hills and the smell of freshly cut homemade bread being toasted. The toaster was often a two-sided gadget on which both sides came down, and only one side of the bread was toasted. Some might recall a coat hanger twisted, moulded, and placed on the old wood stove. It made an inventive device for toasting bread but required constant supervision; the kitchen could quickly fill with smoke from burning toast. A cup of instant coffee or freshly steeped tea would help wash down the toast. Outside we’d listen for the familiar morning sounds: a mixture of seagulls, steering, crows and the putt-putt of the old make-and-break engine echoing off the harbour cliffs as the first boats returned.

Down Below we’d run to the wharves shouting. “They’re, coming by’s! They’re coming!” We were so excited that our feet would barely touch the landing as we leaped onto the wharf. Rushing to the head of the wharf, we’d catch the rope as it was being slung ashore. The putt-putt engine would fall silent as the boat sliced through the water and pulled alongside.

“How much did you get?”

“Can we prong it up?”

“Did you get the big one?”

A hundred questions before they could get ashore. Often the answer was “Yes.”

With the prong in our hands, we’d jump onto the gangboards and soon fish stabbed with the prong flew from the boat to the head of the wharf. Another person stabbed and dragged the fish over the wharf and into the stage, placing it into the fish box. After the cod was unloaded and taken out of the morning sun, we joined Dad and his crew, helping to finish their lunch.

Then, the cleaning of the fish began. The fish was removed from the box by a person known as the “cut-throat.” He would slice the throat and slit the fish down the belly, then slide it to the person called “the gutter,” who removed the guts, skillfully separating the liver from the puddick and pushing both in separate directions. The liver landed in the blubber barrel, and the puddick fell through a hole in the floor. The water churned with a feeding frenzy of tomcods, cunners and flatfish.

Meanwhile, back inside the stage, the head was removed and allowed to fall onto the floor, where one of us would quickly retrieve it and cut out the tongues and cheeks, or sometimes make it into cod heads. The remaining fish went to the “splitter,” the most highly valued man on the line. A good splitter could quickly remove the sound bone with a loud thud as the bone hit the side of the stage. The fish fell from the splitting table into a puncheon tub of water. This process repeated itself until all the fish was cleaned.

Being young, full of energy and unable to stay focused, we’d eventually lose interest in the work and wander off to catch tomcods, cunners and other fish alongside the wharf. We imagined ourselves to be great fishermen, on the waters searching for the big ones as we baited our hooks with hearts collected from underneath the splitting table. Tomcods were quickly caught and removed, but the prickly cunners required more skill to avoid stabbing the fingers. Often the poor cunner would be banged against the wharf or the side of the stage to remove it from the hook.

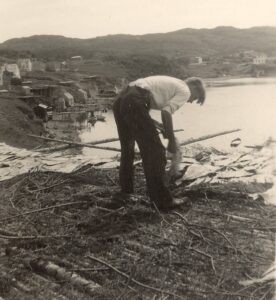

Azariah King, Clarence King, and Ralph Drodge hauling a codtrap off Hatchet Cove. Courtesy Clarence King.

The work continued inside the stage, where Dad would remove the split fish from the puncheon tub using a dipnet, take it to the back part of the stage, lay the fish down flat, and place salt on top. Extra salt would be placed on top of the fish to help with curing. The process would be repeated until all fish were salted in the back of the stage. It would be stored here until later in the summer, when it would be removed and placed on the flakes to dry.

The rest of the crew would clean the stage by drawing buckets of water and splashing them on the floor, table, wharf and boat. Sometimes an old wooden broom was used to scrub the boards clean.

After the fish was cleaned and salted, and stage washed, Dad would shout, “Time to go. Put away the poles until tomorrow.”

Down Below – PDF – Downhome Article

_____________________________________

Transcribed by Wanda Garrett, January 2026.

These transcriptions may contain human errors. As always, confirm these as you would any other source material